Manuscript excerpts

EXCERPT #ONE FROM CHAPTER ONE

Brno is the second city of Czechoslovakia, but it was my father's first, where he was born on March 23, 1932. He came from a loving prosperous non-practicing Jewish family. But after the Germans invaded Czechoslovakia, my father found himself separated from most of his family and in hiding from the Nazis. Just a little boy at the time, his was a childhood lost and hardly ever spoken of again. It wasn't until decades later at the urging of my mother, Rhoda Seidler, that he wrote a few pages to recount for his daughters and grandsons the untold story of his Brno childhood and the war years in France and Switzerland he could never bring himself to speak about.

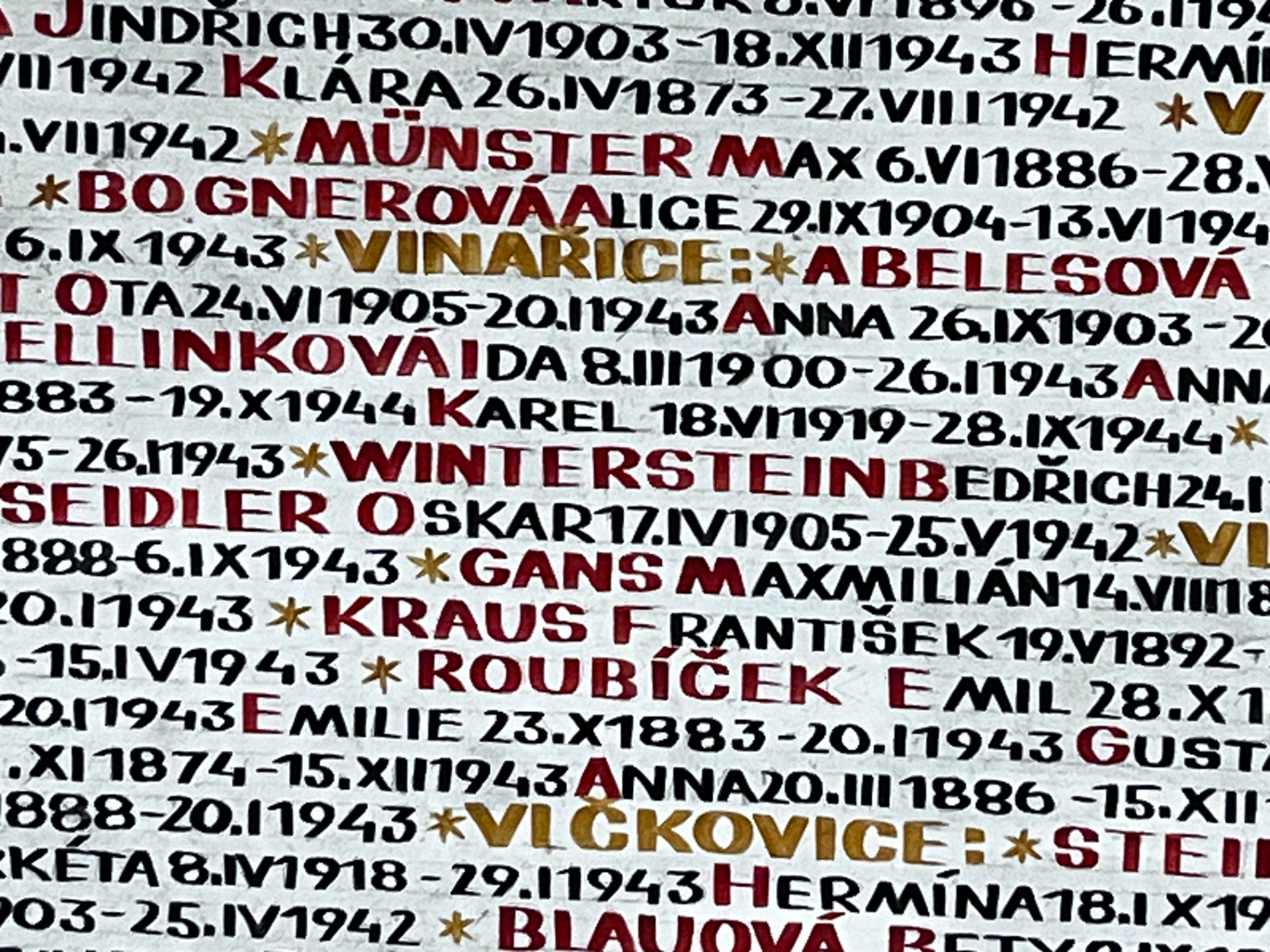

I was born Eduard Alfred[1] in March 1932 in what I remembered as a villa No. 31 on Tivoli Street[2] in Brno, also known as Brünn, Czechoslovakia, and owned by my parents. I discovered, visiting in 1990 this "villa," that what I thought was an individual house was in fact one in a series of terraced houses, with a garden at the back. My parents [Oskar and Hélène] lived on the second floor, my uncle [Erich]'s family on the third, and the housekeepers on the first. I also have a vague memory of the textile factory that my parents owned (my father oversaw the commercial aspect of the business; my mother was the "pattern maker").[3]

I was able to track down the address of this textile factory in a online document describing the forced sale of my grandparents' business during the Nazi occupation. The location has since been confirmed by Milan Kuksa whom I met during my stay in Brno in September 2019 (see chapter fourteen). I had actually walked right by this building — Bratislavská 31 — several times during my short time in Brno without any idea that it had been my grandparents' workplace!

[1] Eduard after his maternal grandfather and Alfred after his paternal grandfather.

[2] Tivoli street was renamed Jiráskova. Names of streets in Czechoslovakia were originally German, the main language used in the era of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. They were then changed to Czech names after WWI and again to German names during World War Two. They have all regained their Czech names, since the liberation of the country in 1945.

[3] As noted earlier, several documents relating to this factory actually refer to a "knitting factory," which I only found out long after choosing the knitting imagery for this book.

EXCERPT #TWO FROM CHAPTER THREE

Forced Labor: My Second Wrong Assumption

At least one thing seemed certain: Oskar had been doing (forced) manual labor since at least February 1941, when he wrote a letter to his son alluding in vague terms to his farm work, the details of which are made clearer in a letter written the following month from a place he calls "Fryš.": "I have a lot of work with the fields, chopping and sawing wood, shredding, cleaning seeds, carrying sacks and many other things." The letter ends on a note of poignant optimism, "But as long as the sun, moon, stars, trees, plants and animals exist, my joy remains." (The letters are transcribed in full further in chapter five.)

I originally accepted the fact that Oskar had written both of these letters to my father from a labor camp. That seemed enough information for me then, until I realized that I didn't fully understand what that entailed. I didn't know what Oskar's journey and living conditions might have been after his factory was taken from him. What had happened between his last letter from Brno and the one from "Fryš." dated March 31, 1941 ? The content of the letter, which is reproduced in full on page 48, seems proof enough that he worked in agriculture in "Fryš.". I believed "Fryš." to be short for "Fryšták," a town on the east side of Moravia, 30 kilometers or so from the town of Vlachovice—the town that was listed as Oskar's last residence before he was deported from the town of Třebíč, on the west side of Moravia. My curiosity about these few months that were unaccounted for continued to grow.

I started researching the topic of forced labor in the Protectorate between 1939 and April 1942, when Oskar was eventually deported from Třebíč to the concentration camp of Terezín. My digging led me to understand that there wasn't just one scenario when it came to Jewish forced labor. Any work Jews had to perform at that time can be considered to be forced in that they had been deprived of their actual jobs and were obligated to seek other (usually manual) employment for which they often had to retrain.

I was aware that the Czech government had, without being prompted by the Nazis, stripped the Jews of their right to work in most professions, excluding them from the Czech economic system by applying its version of the German Nuremberg Laws. At that point, Jews who had lost their livelihood had been made to register as unemployed. What I didn't realize was that 'labor' took on several forms, each of which was directly linked to the emigration expectations, policies, and failures of the Protectorate at various times during the war years. Forced labor was one of the responses to Jews' enforced unemployment, an irony of ironies!

EXCERPT #THREE FROM CHAPTER FOUR

It came as a great surprise that Karen Kruger's documentary about her grandparents, Letters from Brno, was able to answer questions about my own grandfather Oskar, who as it turns out was first cousins with Karen's grandfather, Armin Türkl. And yet, I had never heard of him! In her film, Karen pieces together her family's story through letters and photos she discovered after the death of her mother's aunt, Marianne Schindler, who had looked after Karen's mother, Erika, and her mother's sister, Daisy, in the United States after the war. It wasn't until her mother's death that Karen delved into the letters, photos and documents she had been given. She explained to me that her mother never told her children when they were growing up that she was Jewish. It was only by happenstance that they found out from their uncle when Karen was a freshman in college. But even then, Erika refused to talk to her family about her origins and the painful events of her childhood.

Thanks to Karen's documentary, some of the questions I had been asking myself about Oskar were addressed; I never dreamt that the answers would materialize in letters from my own relatives, Armin, my grandfather's first cousin, and his wife, Herta, who had done all they could to emigrate. The letters Karen's grandparents wrote made me think that the life I had pictured for my grandfather might have been completely different to the actual truth. If Oskar's experience was in any way similar to the Türkls', he also could have tried, unsuccessfully, to leave Brno. Not only do these letters reveal how difficult the emigration process was logistically and financially, but they also expose the emotional side of the burden, in a way history books could not.

Sir Nicholas Winton, a British stockbroker and humanitarian who helped Czech children escape the Protectorate, was instrumental in saving the lives of Karen's mother and aunt. They were able to leave for England with Winton's Kindertransport. More will be said about the Kindertransport in a later chapter. For now, I want to quote some of Karen's grandfather Armin's letters that shed light on the endless efforts of parents to reunite with their children. For Armin and Herta Türkl the longed-for reunion sadly never took place as both were murdered in the Holocaust.

The letters I quote are here those that enabled me to better understand what must have been my grandfather's struggles to survive in a world where he was no longer welcome. Like most of the letters found in this book, the excerpts in this section intend not only to clarify my own family's story, but also the greater narrative of the other Jewish people who were victim of the same circumstances.

Tivoli 31

I started to watch Karen's documentary and was immediately struck by one detail: as a narrator read out the English translation of one of Armin's letters, an envelope appeared on the screen. It was most likely the envelope of the letter being read. Its return address was Tivoli 31. Tivoli 31 was also my grandparents' and my father Édouard's address and that of my father's uncle, Erich, and his family!

I found out from the letters Karen later showed me that Armin and Herta were close to Erich. The feeling of closeness was mutual; in a post-war letter to Armin's sister-in-law, Marianne, dated September 5, 1945, Erich writes that Armin and his wife Herta were "like brother and sister to me." I wondered if Armin and Herta had also been close to Oskar in 1939—close enough for them to move in with him. But did Armin and Herta actually move in with Oskar? If so, was it by choice or by necessity? Or perhaps the house belonged to Armin as well as to Erich and Oskar?

I didn't think I would ever find out with certainty why Armin had indicated Tivoli 31 as the return address on his envelope and reached out to Michael Fuhrmann, my third cousin and author of our family tree (see annexes). Michael explained to me that Tivoli 31 had been in the family for several generations. It had been owned by the Brno Placzek patriarch, Baruch, who was not only Erich and Oskar's grandfather, but also Armin's.