How my journey started

(Introduction to my manuscript)

"Behind every name, a story"

(Yad Vashem)

"This could make for an interesting book" (my grandmother, Hélène Seidler, 1989)

A stitch at a time to weave your story, you whom I miss so much and whom I'm discovering a little, or rather a lot, in this journey that was yours and that I try, one stitch at a time to reconstruct, to retrace, realizing at the same time my own journey filled with discoveries, surprises, and extraordinary people.

In a way, I am weaving or knitting a story like my grandmother Hélène ("Lene", "Lena"), who knitted socks for the Agen[1] rugby team during World War II, earning barely enough to support her family during those years. Was this the source of my father's passion for rugby? Was it what inspired him to become a sports journalist at L'Équipe, France's only daily sports newspaper?[2] This imagery of intertwined stitches seems to me to perfectly describe the detective work in this book. A friend likened it to a tapestry or a spiderweb, as stories seemed to grow out of the center of the project. I will use that imagery to reconstitute the episodes of my father's life during the war and that of others I met during my research. If the links between these "characters" and the events recounted seem at times to fit together logically and naturally, at other times they seem to be more of a miracle!

The pattern of my project wasn't formed right away; it was a few years before it started to take shape in my mind. How, or rather when, did the desire to tell this story, our story, surface within me? Even though my mother, Rhoda, had asked my father, Édouard, to write about his childhood a few years before his death in 2010 and shared with me the few pages he had written, I had little interest in them at the time; I was busy raising children and building a career. I regret that now. Had I read the pages when my father was still alive, I would have had the chance to ask him questions and learn more about his childhood as a young refugee in hiding from the Nazis. Perhaps this book is an attempt to answer all the questions I never got to ask.

A couple of years after my father's death, my mother gave me a box full of letters of correspondence between my father and his mother, Hélène, during and after the war as well as school reports, refugee cards, rationing cards and other priceless documents that Hélène had amazingly managed to save all those years. How had she held on to them? I couldn't say… I found out later that she had given them all to my father in 1989 but I had never seen them before. Some of the letters were written in German but most were in French; as a native French speaker, I had no difficulty understanding the four or five letters I took the time to read. As for the German letters, I had enough knowledge of the language to know when I needed help from a native speaker to better understand the details and subtleties of the letters. I asked my former German colleague, Christiane Pyle, who kindly translated a few of the letters for me. She later inquired: "Aren't you going to do anything with your father's letters?" But still submerged in career and family, I put the cache of letters aside.

In 2019, I was due for a sabbatical leave—which as a university professor I have the option of taking every seven years to conduct research. As a sabbatical applicant I would need to come up with an original research project to be approved by a review committee. The process can be rather involved and as I was pondering what project to propose, Christiane's question came back to me: "Aren't you going to do anything with your father's letters?". That was the defining moment, when I decided that I could use my sabbatical leave as a golden opportunity to research and tell my father's story. That's when I began to get excited about delving into the letters I had been given years earlier and learning more about my family—a family that I had barely known, many of whose members perished in the Holocaust.

I started putting my sabbatical application together. At that point, I knew very little about my father's experiences and next to nothing about the relevant historical facts, which I put down to a lack of education during my school years about what really happened in France during World War Two, especially about Vichy and the French government's collaboration with the Nazis. So although the members of the sabbatical committee thought my topic worth investigating, I would need to produce a more substantial application to win approval.

I began to thoroughly investigate the events of World War Two in France—in particular the Holocaust and how it pertained to my family's history. I quickly realized that what I thought had been unique to the Seidlers' experiences had been similarly shared by many others. My father's story thus became part of a much larger narrative.

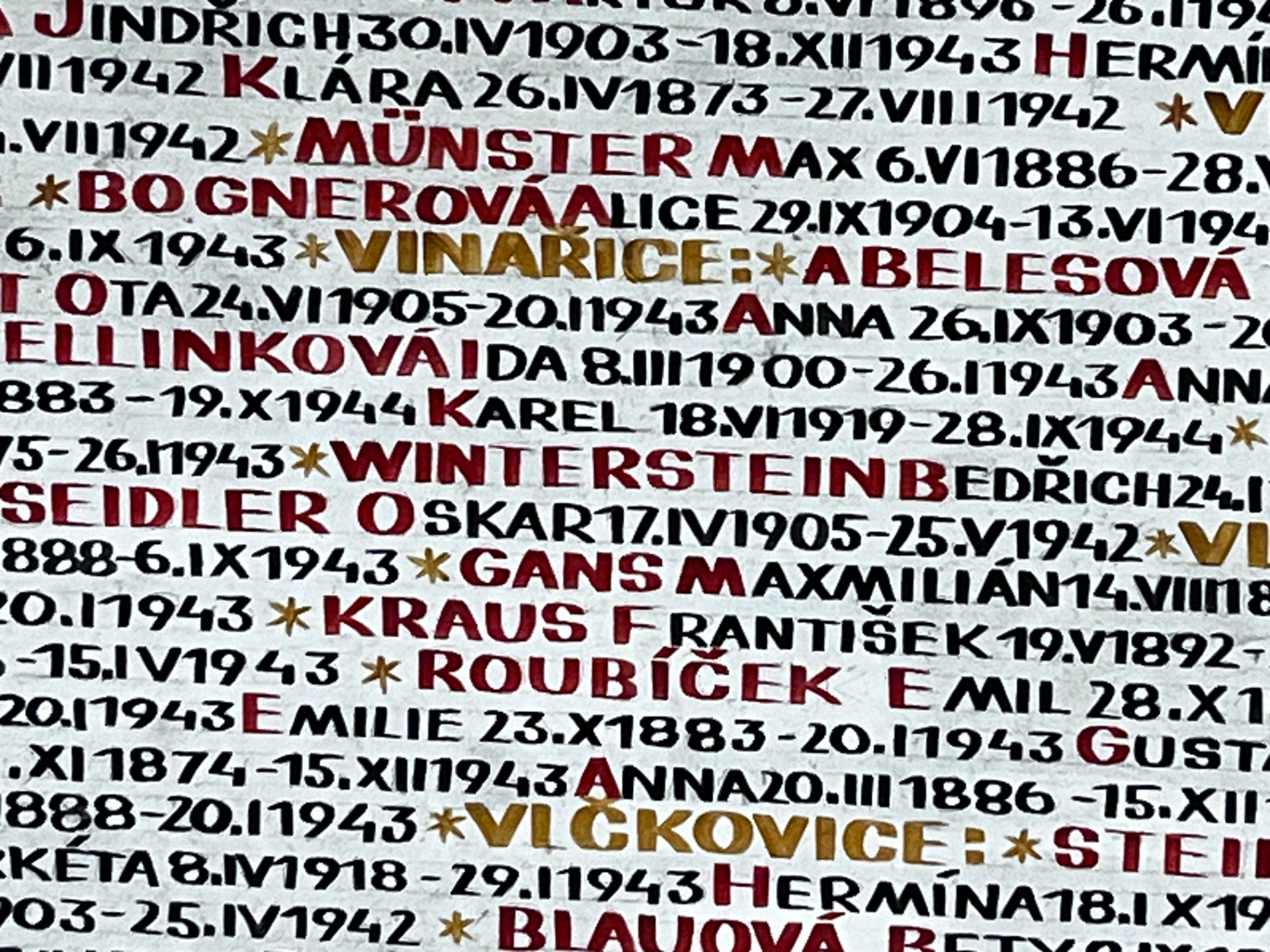

I started by compiling a document filled with dates, events, characters, but it was Yad Vashem, a memorial to the victims of the Holocaust in Jerusalem, that gave me the words I had been missing, "Behind every name, a story" to convince the sabbatical committee (and perhaps myself as well) of the worthiness of my research. And so I concluded my proposal with the words: "My name is Marianne and I have a story to tell."

The project was unanimously approved. And off I was, on a journey that led me from one discovery to another! From that day on, names, events and places filled my waking thoughts and dreams.

Édouard, Hélène, Lisette, Oskar, Georg, Goa, Anda, these are the names of the main characters in the story of my family; each one of them with a story to tell, the story we share as a family. Alice, Menachem, Bernard, Ron, Rose, Robert are the names of characters who appeared unexpectedly, and who with their revelations contributed to my understanding of what ordinary people had to endure during the war, so that I could do justice to the truth.

Indeed, woven into this tale are the extraordinary encounters I made throughout my research. I feel as if I infiltrated a parallel world that has existed for a long time without me in it but one into which I have been welcomed with kindness and generosity. Thanks to the people who inhabit it, the youngest of whom must be 84 years old, I have obtained information, photos and documents that allowed me to paint a more complete picture of the lived experiences of young refugees during the German occupation.

Thinking at the beginning of my project that I would focus solely on the story of my father, Édouard, and his younger sister, Lisette, I could never have imagined that I would meet so many extraordinary people—Jewish refugees, survivors of the Spanish Civil War, historians and researchers, among them—all of whom had some sort of link with the fate of the members of the Seidler family. These encounters moved me to tears and laughter, and filled the empty spaces when my findings were incomplete.

Thanks to these people, what might have been a painful undertaking was carried out in joy: shared meals, conversations, remembrances and emotions that bonded us forever. These encounters enriched my personal and historical research and enabled me to weave together, one stitch at a time, the storybook that begins here.

If this book can touch other readers, I will only be happier for it. So many people whose parents lived through the Holocaust years were unable to tell their story because they never had access to the letters and documents of their vanished family members. But my grandmother left us a treasure that I had to share. In a letter to my father about their journey, she remarked that "This could make for an interesting story." Little did she know that her granddaughter would one day delve into that precious correspondence she managed to hang on to protect while running from the Nazis. I trust it does make an interesting story!

[1] Town in the southwest of France

[2] Newspaper which he subsequently ran from 1980 to 1984 after a decade as its Editorial Director.